There’s more than just one mine in Penzance…

On May 10th, 2022, a large hole suddenly opened up on Polmeere Road. That a suspected mine shaft had appeared in central Penzance really got us thinking. It’s perhaps not common knowledge that actually Penzance was, in a way, its own small mining district, just like the more famous ones of St. Just or Camborne-Redruth. It had its peculiarities and its quirks, its saints and its rogues; all woven into the rich and timeless history of west Cornwall’s largest town, as we know and love it today.

Early Tin Working in Penzance

Predictably, the story starts a long time ago: in fact, to find reference to the very earliest mining in and around Penzance, we must venture to go all the way back to 1270, over 700 years ago when Benedictine monks dwelt in St. Michael's Mount. The Abbey of St. Michael's Mount was paired with its sister house, Mont Saint-Michel, in Normandy and between them they ran a lucrative operation catering for travelling pilgrims. However, the fledgling Abbey needed a stronger footing to secure its long-term financial security.

Besides the Mount, the monks of St. Michael's priory owned several other properties such as the manor of Treboe, at St. Keverne, on the Lizard Peninsula. However, and of most interest for our story in question, they also owned several tin works, one such example being recorded at Trevabyn, near Goldsithney, in the last two decades of the 13th century, 750 years before our present time.

What did this mine look like? Who worked there? How long did it work for? Was it then a new mine, or already an ancient one? We have only questions but not answers. All that we know is that tin was being worked at Goldsithney, in the vicinity of Penzance at an incredibly early date; a legacy that would continue right to 20th century with mines like Wheal Vincent, Owen Vean, and Tregurtha Downs.

In the following centuries, there were a great many tin works in the district around Penzance, and we know this from a series of old mediaeval records. Cornwall’s major tin mining areas were divided into “Stannaries” (from the Latin “stannum”, “tin”) for the purposes of administration and tax collecting, and it is through these legal and financial incentives that accurate and extensive records of this early period have survived.

Many Stannary court rolls (medieval documents) can be found in the national archives at Kew, specifically in the records of the Exchequer; perhaps an appropriate resting place given the riches they returned to British royals. The consultation of these, aided with a good grasp of mediaeval palaeography and Latin grammar, reveals a fascinating portrait of the mediaeval industry.

There were five stannary districts in total: Penwith (in which Penzance was situated), Kerrier, Tywarnhayle, Foweymoor and Blackmoor; with an additional four in Devon centred on Dartmoor. Some excellent research on the Stannaries of Penwith & Kerrier has been undertaken by historian Allen Buckley and can be read about elsewhere. Suffice to say however, the district around Penzance, in the moors around Marazion, in the hills at Madron, and in the vales of Gulval, throughout the intervening centuries between the Trevabyn Tinwork and the Tudors, saw significant mineral exploitation.

Tudor Copper Mining in Penzance

What of the mines not around Penzance, but actually within the present town as we know it today? Well, there were actually quite a number. However, none of these appear to have been tin mines: rather lead, copper, iron, and even a small bit of cobalt. It is a fascinating story and one that deserves tackling each mine individually.

The earliest record of mining in Penzance itself is a document from Hatfield House in Hertfordshire; childhood home to Queen Elizabeth I and later the home of her first Minister William Cecil. This collection is particularly important for learning about the early history of Cornish mining because Cecil, being one of the Queens closest confidants and administrators, was responsible for seeing the expansion of the Tudor machine and the fostering of new industries - then necessary after many important trade links had been lost with Europe in the Reformation.

Elizabeth’s father, Henry VIII, had attempted to encourage the expansion of the British copper, lead, iron, etc. mines during the 1530s with the “Commission for the Mines of Devon and Cornwall”, although this had seen little success. However, the flame once lit was never extinguished and his pursuits were carried on by Queen Mary’s government when she succeeded to the throne in 1553.

England lacked the pedigree of non-stanniferous (non-tin) mining that Europe had been cultivating throughout the mediaeval period, and so she hired several European mining experts to teach and develop the skills within the island nation. Perhaps most famously a German, Burchard Kranich, was active during this period and it is most likely from him that we have to thank for many earliest references to mines in Cornwall.

The map in Hatfield displays the whole of the south-west peninsula, including also a small part of Wales. It is unusually detailed for the period, but upon closer inspection it is of no new pedigree. The map is in fact based on a much older piece of cartography, Ptolemy‘s Geography, of the 3rd and 4th centuries A.D.

The Tudor age saw many great leaps forward in technology and the intellectual arts. But it was a period spanning from the mediaeval to the modern, the beginning of which had seen no new comprehensive detailed mapping of the Britain Isles for over 1000 years. This is a fact that I find astonishing to this day. And it was by the end of the Tudor period that the first new surveys of this country were produced; such as Saxtons in the 1570s, giving rise to what is called the Elizabethan golden age.

Our mineral map at Hatfield, whilst based on cartography 1000 years old, contained all new information as far as mining was concerned. The author, most likely Cecil himself in his own hand, but he was likely taking his information from representatives in Cornwall, or Burchard Kranich directly.

It records all non-tin mineral occurrences in Cornwall then known with little crosses, and mentions the metal in question with the Latin plumbum them or cuperum for lead or copper. Of interest to our story is one of these such marks, as it is placed conspicuously off shore from Penzance and marked copper.

Whether this represents a specific location actually offshore and, in the sea, cannot be known, for as we shall see, there are many other contenders for this 460-year-old copper mine in the Penzance vicinity. That workings were going on in the reign of Queen Mary the first however, is without doubt and it only awaits the job of the local historian find direct records and add flesh to the story.

17th Century Penzance: Setting the Scene

Very little is known about the mines of Penzance during the 17th century. It was during this period Penzance first became incorporated as a borough (in 1614) and as a coinage town (in 1663). A coinage town was a place where tin mined in the district was tested for its quality and taxed.

Penzance was at this time a very small community consisting of just the harbour, the modern-day high street, and the area around St. Mary’s Church. An observer standing on the rocky promontory now known as Jubilee point would have seen a charming little settlement growing outwards from this main road from the harbour. At this stage Lescudjack Hill, Alverton and Wherry town, the situation of much domestic housing today, were barren. Most likely they were occupied by mediaeval strip fields, the Cornish “gweals”, but otherwise not settled besides small farms and isolated houses.

It is from Wherrytown that we get our next reference to mining. Records of the Angarrack Smelting house suggest that workings could have been practiced here as early as 1713, however we know little of what was actually done at this time. What followed however became easily one of the most famous landmarks of far west of Cornwall by the end of the century. This is the story of Wherry Mine, which we will take a deep dive into shortly...

Cornwall and its Minerals

For many hundreds of years, the genesis of Cornwall’s rich minerals was totally unknown to all who worked it, expert and amateur alike. The richest tin and easiest to win was often not found underground but barely beneath the surface in the hydraulic beds of streams and rivers, in much the same situation as one would likely find gold through panning. This is because tin is a very heavy metal element, its specific weight coincidentally being almost identical to that of gold.

This coupled with the richness of its ore, cassiterite, meant that the early tin miners, working in the streambeds, resembled much that of the later gold miners of Klondyke, just many hundreds of years prior. How these tin gravels – stream tin – came to be deposited in such a strange location was often conjectured.

To the mediaeval mind, and indeed right the way through to the advent of modern geological understanding in the late 19th century, it was believed that the tin gravels had been washed into their present positions by that of Noah’s flood. The Bible, being essentially a collection of folk texts widely read during the Roman period, was often referred to for apocryphal knowledge. It is not however a wholly incorrect perspective; for as we know today the gravels were washed into position by the action of water, however the time period in question being much earlier than the Bible could have predicted.

It is through the action of freeze thaw weathering over successive ice ages across the last million years that these mineral veins, once standing at the top of high Granite Hills, were decomposed and eroded; with the remnants coming to rest at the lowest adjacent points in valley bottoms.

One can forgive such conjecturing using Biblical inference, for these stream works as they were known, were almost ubiquitous across Devon and Cornwall during the mediaeval period. In fact, it was the main, if not exclusive, way that tin was worked until the 15th and 16th centuries. It must have been quite unsettling to be so close to something that was so commonplace but so little understood. Indeed, the Bible was the only book with which most people were familiar, it being their only possible source of literary knowledge.

But what of the mineral veins, who contributed so much to the stream works through paleo-environmental weathering, where did they come from? Well, their origins are found in the much more distant geological past, on this scale our many successive ice ages each go by like the blink of an eye. Cornwall’s unusual shape - a promontory that sticks out directly into the Atlantic Sea at the far tip of the British Isles - is due to an unusual presence in our regional geology: Cornish granite.

Known as a batholith, and huge body of granite formed deep beneath the Earth’s surface, it is this igneous rock that has resisted the weathering action of the sea, whereas sedimentary rocks have is been subject to much faster erosion. This granite backbone is a window into the deeper geological processes of the Earth.

Let us delve back in time, to approximately 300 million years ago. The region now known as Cornwall has been underwater for much of the preceding 100 million years or so, and this had led to the slow accumulation of thick layers of mud and sandstone. But this peaceful situation was not set to last.

This area gradually found itself as ground zero for the collision of tectonic plates, the huge fragments of the earth’s crust that, millimetre by millimetre, advance and retreat in an unending jostle for supremacy, ultimately shaping the surface of the earth as they go.

If you set two large plates on a collision course with one another things get messy. Like apocalypse-style messy. Think earthquakes, volcanoes, and so on. Finally, you end up with the plates crumpling into each other, with nowhere else to go but skyward – you get the formation of mountains.

And that’s just what happened to what is now Cornwall about 300 million years ago. Geologist have weighted the evidence and deduced that there was a mountain range some 5000 metres high occupying southwest England. Pictures a mountain range on the scale of the Andes. The tors of Cornwall and Devon are all that remains of these once majestic peaks. This was a truly global event, and coincides with mountain-building episodes around the world, such as the Appalachian Mountains, for example.

The photo below was taken on Aconcagua, the highest peak in the Andes mountains. Did a mountain range like this once exist in Cornwall?

Far beneath the surface, the temperature and pressure simply got too much, and a colossal body of magma was formed. This was the Cornubian batholith and it extended from Dartmoor to the Isles of Scilly, and beyond. Huge plumes of molten granite sought their way upward from the main batholith in huge cuppolas, and it is these cuppolas that form the exposures of granite we know today, and include the Isles of Scilly, Land’s End, Tregonning-Godolphin Granite, Carnmenellis, and the St. Austell, Bodmin Moor, and Dartmoor plutons.

These cataclysmic events also led to the formation of all the major mineralisation in Cornwall and Devon. Huge cracks, known as faults, were created, and these were rapidly infilled by whatever cocktails of mineral were most volatile, and were trying to escape their granite prison. Over the aeons that followed, these fluids cooled and solidified, forming mineral veins. And if these mineral veins were found to be of economic worth by miners, tens of millions of years later, they were named ‘lodes’.

Those poor mud and sandstones that existed before the granite, were subjected to folding, faulting, and regional metamorphism, and were turned into rocks with familiar names like slate. The Cornish miners called anything that wasn’t granite, essentially, ‘killas’. The mineral veins emanating out from the granite, made their way well into the killas too, and thus many of Cornwall’s mines are hewn in areas where the bedrock is entirely killas, with no granite to be seen.

With this in mind we can start to understand the layout of the mining that we see in West Cornwall. Camborne and Redruth flank the granite hill of the Carnmenellis granite; Godolphin and Great Work mines saddle the famous granite hill of Tregonning near Breage; and the world-famous mines of St. Just are on the coastline not by coincidence, but because this is the intersection between the Land’s End granite and the metasedimentary rocks which forms the shape of the west Cornwall as we know it. Is it then any wonder that there are more submarine mines in St. Just than the rest of the country combined?

Levant was probably the most famous of these and for good reason: its working is extended over 1 mile beyond the coastline and deep beneath the Atlantic Ocean. And all of this in the Victorian era, worked by hand and through the light of a candle: an astonishing achievement even today, let alone for its own time.

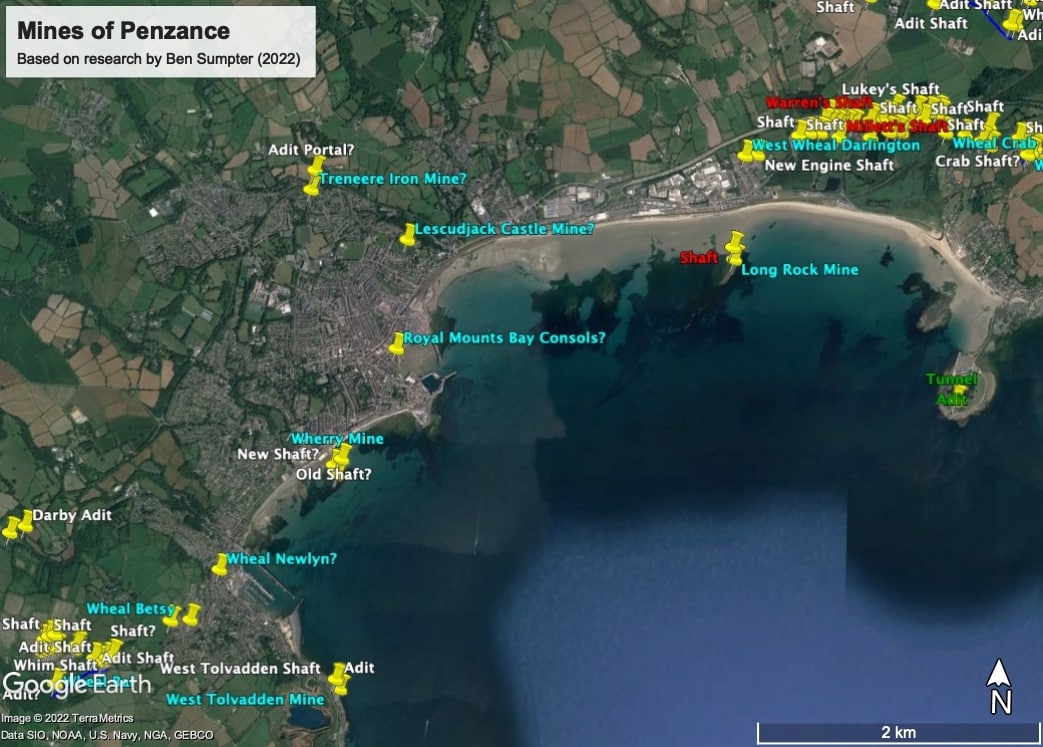

But it was by no means the only submarine mine in the district. To name a few, there was Cape Cornwall mine, Wheal Call, Wheal Edward, Wheal Owles, Botallack, Wheal Cock, Wheal Unity, Geevor , Boscaswell, Pendeen Consols and Wheal Hermon! What is less well known, however, is that Penzance itself had its own submarine mining ventures; two that we know of at Wherrytown and at Long Rock.

Penzance’s Most Famous Mine: Wherry Mine

The early history of Wherry Mine we have alluded to, both in that apocryphal Tudor document and also in the more specific smelting records from the early 18th century. The first time of which Wherry truly takes the spotlight however is in the late 18th century.

The knowledge of minerals in the district had clearly never been lost and the local miner, Thomas Curtis, had been given cause through poverty to turn his attentions to an igneous vein of rock, known as an Elvan dyke, running parallel to the shore opposite Penzance at Wherry Town. It is likely that many locals before him had noticed the presence of tin in this unusual piece of geology and had from time to time chipped away at it with hand tools at the very lowest spring tides.

Thus, this was the limiting factor: its distance from the high tide mark, some 250 yards, meant that efficient working of the ultimately very rich deposit was almost impossible and always limited by the rising tide. This is what triggered Curtis to an incredible feat of ingenuity.

The supposition was that if a wooden box, lacquered and tarred to be watertight, could be built upon the dyke, it would facilitate the sinking of an offshore, and submarine, shaft into the rock and for workings to be carried out underneath the seabed, which through the aid of pumping would remain dry throughout the tidal cycle.

The challenges were obvious and manifold; that Curtis succeeded in pulling them off his nothing less than incredible. The wooden box had to be over 20 feet tall to prevent the highest tides from inundating the workings below, and it had to be braced so that it was secure even in the roughest of Atlantic gales.

Originally miners rowed out to the structure in boats, known as wherries, and this is what gave the mine its name. Presumably if their little boats became untethered, they were stranded there until the tide fell or they chose to swim back to shore. There can be few ventures on this earth that can lay claim to such daring, such engineering, and such foolhardiness.

Wherry mine worked what is known as a “stanniferous elvan”, its unusual quality being that it looks very similar to granite rock but the tourmaline (little black spots) had been replaced by rich and valuable tin. Another unusual mineral that was also encountered was that of cobalt, very rare even in Cornwall, and indeed today some of the very best mineral specimens of this fundamental element come from the 18th century workings of this mine.

From the 1780s through to the 1790s The mine went from strength to strength and was eventually acquired under new management and worked in collaboration with Boulton and Watt, the famous engineers you see framed on the back of the old paper £50 note; and one of their steam engines was erected. It is from their correspondence that we can derive most of the history of the mine from this period.

Originally a wooden shaft and an isolated platform was built 250yrds directly on top of the elvan itself. To access this and to facilitate pumping, A timber bridge or trestle was constructed the whole length of the over water passage, which additionally allowed mules to haul carts of ore back to the dressing floors on the land.

It also had the ancillary, and perhaps intended, purpose of becoming a local landmark and a tourist attraction for those wishing to promenade. Perhaps this is the origin of the promenade at Penzance today? It was certainly an attractive allure for burgeoning honeypots like Brighton over following 100 years.

It was this capacity for Wherry mine to turn heads and attract attention which has cemented its legacy in the history of Penzance to this day. And most importantly, it is to which we owe our first visual representations of mining in Penzance; a series of two pictures, both based on paintings which depict an attractive and charming view of the little town perched on its headland looking out towards Mounts Bay and St. Michaels mount; but framed front and centre is this astonishing engineering achievement of submarine mining, the crowning jewel of the scene.

Mining today does not have a universal appeal; however, these examples of precocious engineering ingenuity challenge us and our assumptions about Cornwall’s most famous industry, and perhaps greatest achievement.

The uniqueness of Wherry’s beginnings was only matched by its quizzical end. Penzance grow around its harbour and throughout the period of Wherry’s growth, the harbours of the borough and those of Newlyn, Mousehole and the Mount all saw their growth likewise. What this meant was that the waters around Wherry were busy highways; vessels coming and going, local and foreign, national and international.

It was the latter most that was to see the end of this first phase of Wherry’s history. In a particularly violent storm, an American vessel moored in Newlyn harbour broke its fastenings (they were of course or made of hemp ropes backs then) and was set adrift in the waters off Wherrytown. Having eventually collided with the wooden shaft offshore and at high tide the mine was flooded; as it so happened, irreversibly.

The price of tin was low, and it was not deemed worth the cost of repairs to reopen her. By this stage presumably the intrepid adventurer and mastermind of the project, Thomas Curtis, must perhaps have in his later years and no longer an active part of the project. Perhaps he saw the full life cycle of what he had started, earliest beginnings working at the spring low tides, to national renown and rich investment.

What must he, a local Cornish man of humble stock, living in the time (and town!) of Dolly Pentreath, have thought of his career and his achievements? These are reflections I as an historian and would dearly have loved to have known.

Wherry Mine v2.0

The story of Wherry was not however closed, rather a generation later the memory of such great achievements had not been forgotten and the new chapter was opened. This occurred in, though perhaps without much of the original sentiment, during the 1830s; this time not by locals but by a London company.

It is said that all fame is good fame, and where there is fame there is money. It was perhaps this renown of the original Wherry mine that the new company which wished to capitalise upon by reopening the venture. Certainly, locals were not involved with the management and the project, and this being considered, perhaps it had little ultimate chance of success.

Early mining in Cornwall tended to be undertaken by small groups of local people, at a small or no capital investment basis. It was a way for local people to generate a small, scalable, but lucrative income, in parallel with, or instead of, in the normal forms of rural livelihood, such as fishing or farming. This meant that the earliest mines were extensions of this philosophy: small and low-budget; efficiency was everything.

It is a little-known fact that most mines in Cornwall never turned a profit, yet they did attract a wealth of outside investment on account of the share prospectuses. The reputation of the few very rich and wealthy mines, such as Dolcoath, Levant, & Gwennap Consols gave credibility to a great many more spurious trials which justified lavish expenditure of shareholder money.

In 1860 it was said that, “More money could be made through idle speculation then by hard graft with a pick”. One could make a very agreeable personal livelihood out of attracting such investment and ultimately delivering very little mineral production, the only risk being that to the investors. Perhaps this is a legacy that remains unchanged to this day.

Little is known of the second attempt to work Wherry, but we do know it was short-lived and by-in-large, recreated the engineering that was seen during its first phase, but with new equipment. It is also said a new shaft was sunk and the old shaft sealed, as it was so far from the shore and difficult to work upon, a testament to Curtis’s earlier determination.

Perhaps, although we cannot know, the reopening of mine was accompanied by a great community celebration, recreating a past and nostalgic ideal when the town was famous and attracted investors and tourists alike. Perhaps it was this first taste of tourism that planted the seeds for what Penzance has become today. One can only suppose that the notoriety of Wherry mine must have contributed, at the very least.

Wherry has never been reworked since this last phase during the early Victorian era, however in the 1960s some prospecting work was done on the stanniferous elvan dyke in the hope that modern techniques could extract yet more minerals in. To facilitate this, the original timber trestle walkway to the shaft was recreated but this time using scaffolding, and a diamond drill rig established to test for valuable minerals previously out of reach to earlier miners.

The results have never been published. Could it be that just a couple hundred yards offshore, parallel to the present-day promenade is a valuable treasure trove of minerals waiting to be exploited by the next modern-day Thomas Curtis? That, ladies and gentlemen, will have to be a story for another day.

Penzance’s Other Submarine Mine: Long Rock Mine

As we have already mentioned Wherry mine was not the only submarine venture in the district, even if it was the most famous. Another, although it is scarcely possible to believe today, would also be in carried out at the same time period at Long Rock, directly opposite the beach car park and industrial estate. Its earliest beginnings are apocryphal, perhaps relating to that period in the 1560s when minerals were known to be in the Penzance area.

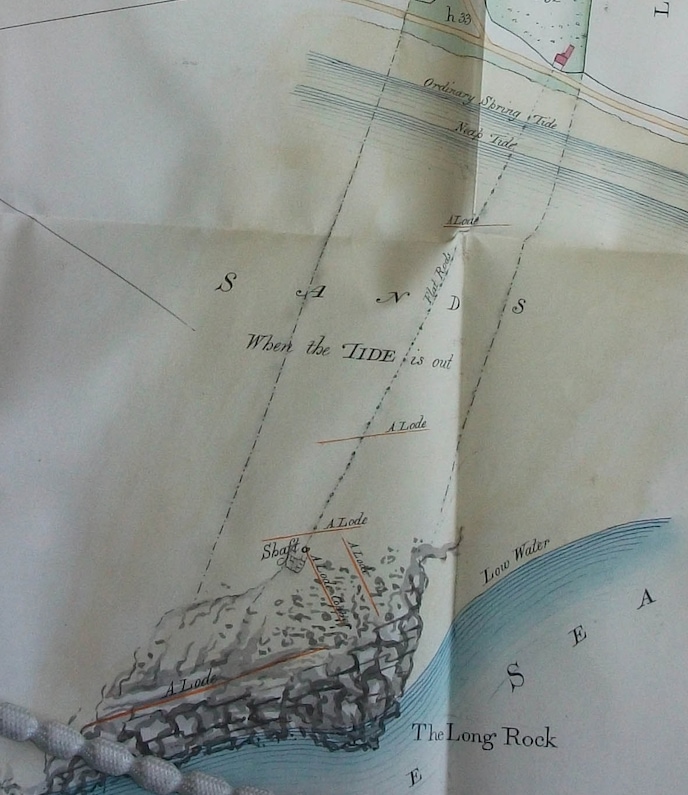

The earliest records we have suggest the mine was at work between 1819 and 1823. Its earliest graphical depiction comes from a map of 1832, showing the interests of the Buller family of Redruth in the manor of Carva. Shown here is a narrow strip of land extending from the Long Rock itself inland, however it is particularly unusual to see so much focus placed on what would otherwise be an insignificant seaside rock.

In this case the explanation is obvious: shown criss-crossing the rock are half a dozen mineral veins or lodes both of tin and copper; a very valuable combination. There is not much indication of how or to what extent they were worked. It is clear that this map places an enhanced focus on this little property because of the fame afforded to Wherry mine, its workings being just a few miles away.

Long rock mine saw its most important phase of working at the same time Wherry saw its nadir. At this stage it was named Wheal Mexico, perhaps taking its name from the pub in Long Rock: the Mexico Inn, or even giving its name to the pub.

This name was a reference to the Cornish diaspora where miners travelled to far-flung regions of the globe, where their skills were highly sought after in the new and developing foreign ore fields. To this day places in Canada. Australia, the United States and Mexico all sports Cornish emigrant communities, and perhaps share the same lineage as us locals if one looks back far enough.

Perhaps taking it inspiration from Wherry, Wheal Mexico set about on a very similar principle of working. The Long Rock is an equally formidable location for mining, being several hundred yards out to sea, fully submerged at all high tides, and only exposed fully during the lowest springs.

Thus, it was essential to construct another timber shaft and platform initially to make underground, and submarine working is possible. However, where Wherry town is sheltered by the haven of Newlyn, the Long Rock is far more exposed. A break water of hard granite rocks was constructed around the wooden shaft, and this survives to this day.

To pump the underground workings, a steam engine was built in a little engine house on the foreshore adjacent to where the pub is now. From here its reciprocal pumping motion was communicated to plunger lifts in the shaft via what was known as flat rods. As the piston of the steam engine went in and out, it was made to push and pull a series of wooden beams, all connected with rocking hinges, and this meant that the power of the engine could be brought along distance to where it was most useful.

The timber frame that supported these flat rods had to extend a very long distance across the sandy foreshore before it reached the rock itself, and this needing to be kept well above the waterline, was suspended by large wooden A-frames throughout the whole distance. And what is most incredible is that over 160 years later, the bases of these timbers still survive and can be found, if one knows where to look, protruding from the sand today.

They can also be seen, a testament to how technology and has advanced, from space and in the form of online satellite imagery. Perhaps stop and think about this remarkable yet scarcely known legacy next time you walk upon those golden sands at Long Rock and chance upon one of those humble little pieces of timber that is hidden in plain sight.

Long rock very much built on the successes of Wherry and in turn it went on to inspire many other small ventures in the district to entertain similar ambitions. Throughout the early 19th century there are records of at least three small trials of other submarine mining attempts in and around Penzance. In 1817 a lease was acquired from the Duchy of Cornwall to work minerals on the foreshore opposite tai Chyandour.

Another was proposed near the rocks at what is now Jubilee point. And the final in 1847 was begun and a small shaft sunk near the harbour at the site of the old gas works, the shaft intending to facilitate exploration of submarine loads. This latter little venture, given its commencement date, decided to style itself Royal mounts Bay consoles, a homage to Queen Victoria‘s royal visit to Mount Bay in September 1846.

In northeast Cornwall, Restormel Mine had changed its style to Royal the year prior, having actually received a direct visit by Victoria and Albert where they actually went underground and explored the workings. This is recorded in her diaries which are now available online. Note that, there is no suggestion that Victoria or Albert visited “Royal” Mounts Bay Mine during the same visit; most likely this was again a promotional tactic intended to make mine more attractive for outside and distant investment. It has but a fleeting part in the history of Penzance but stands testament to a fascinating and exemplary story of the town.

Inland there were no fewer mines in and around Penzance. Perhaps one of the best known amongst locals and historians, was to be found in Newlyn. It was worked under various names, Wheal Newlyn, Wheal Elizabeth, but most famously Wheal Betsy. During the 1840s this little mine, in a most unusual position perched atop Paul Hill, with its engine house, must have looked very similar to how Paul Church looks today.

The workings were not extensive, only 10 fathoms deep, and we do not know how much, or even if, it produced copper during its short working phases. Of what we can be sure however, is its effect on the local community as its legacy survives in the naming of “Adit Lane” on Paul Hill to this day.

Another small mine existed underneath the Penalver housing estate as it rises up the Lescudjack Hill. It is hard to see today, but the hill is an ideal observation point for the natural havens of Gwavas Lake (the sea haven around Penzance) and also, at least in the mind of the early British peoples, easily defensible.

For this reason, during the Iron Age some 2500 thousand years ago a hillfort, incorporating a high circular ditch and embankment crowning the crest, was built. In this, the local tribespeople would have lived and kept livestock, perhaps even defended themselves from other tribes during raids. This and the similar round at the Lesingey both stand testament to the Iron Age communities living in Penzance 2500 thousand years ago.

These sites, given their defensive connotations, are often known by the euphemism of castles and it is underneath this Lescudjack Castle (now a public green and allotments) that a little tin and copper mine is known to have been working in 1723. We know nothing of the nature of its workings or for how long it continued. However, in the 1950s it was known that there was often subsidence around the area of the present day train station and one can perhaps infer that the main workings of the mine extended from this point right across and into the hillside. If this is the case, these were very considerable mine workings indeed, and beneath what is now an important suburb of the town.

Treneere Mine

So having completed our tour of the local vicinity, we are finally taken us to our intended destination, having admired all the sights and stories along the way. Which mine did the shaft, which so surprisingly revealed itself in Polmeere Road, belong to?

In 1935 and at Treneere House, now the back of Penwith College where it meets Manor Way/Coombe Lane, an old mine shaft was uncovered and soon covered over. It was said to connect with an adit, or drainage tunnel heading from thence northward to the foot of the then, rural valley adjacent Treneere Mill. Its entrance/exit was presumably near the modern-day Parc Mellan Close. Additionally, in 1957 old mine workings were said to have been found in a field at Lower Poltair near Heamoor, and in 1906 “Old Men’s Workings” were to have been found betwixt Penzance Cemetery and the Cricket ground.

However perhaps the most likely contender for the shaft at Polmeere Road can be found in an advertisement in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, dated 15th August 1829. A leasehold portion of the land at Treneere Barton was to be offered for sale by Penzance solicitors Samual & George D. John, and importantly for our story, included in this property was a “Mine of Tin & Copper”. We have no further description of its workings, but it was said to be ideally situated, only “Half a mile from Penznace” (for the old Penzance was just the harbour town) “and the same from two Smelting Houses” (i.e. Chyandour and Trereife, although the latter is much further away).

On what auspice these workings, which must have entailed considerable effort in working, were continued it is not known. Local tradition tells of an “iron mine” in the district, however this is not likely as there are no other like workings in the area. Old adits in Cornwall often secrete a form of bright orange mud known as ochre which contains quantities of iron sulphides, perhaps this is where the rumours started. In reality, the “tin & copper mine” described in 1829 is a much more likely candidate; mine workings of those metals often also ooze iron sulphides, even if iron itself was not the metal being exploited.

If this is true, then perhaps the “Treneere Tin & Copper Mine” was a continuation of the mineral lode that the Lescudjack Castle Mine also worked back in the early 18th century: it could even be that it was a section of the aforementioned mine itself. We can speculate. But that it represents a legacy of mining 700 years old and taking Penzance to the very forefront of engineering and social achievement is hopefully demonstrated in this short article on this most interesting aspect of history.

Ben Sumpter, Helston, May 12th, 2022 (Geolgical History by Matt George)

References:

- Hull P 1962 “Cartulary of St Michaels Mount” Devon & Cornwall Records Society

- Buckley J A 2009 “The Tudor Tin Industry” Penhellick

- [Hatfield House Mss] CPM Supp 1 Map of Southwest England, by William Cecil? c1560s

- Joseph P, 2008 “A New Look at Wherry Mine” Journal of the Trevithick Society

- Jenkin A K H 1962 “Mines & Miners of Cornwall Vol.4: Penzance to Mounts Bay”

- [Cornish Archives Service] X745 Brooke Index for Cornwall

- [Cornish Archives Service] BU/1169 Plan of Tolver (Long Rock), Manor of Carva, by J H Rutger 1832